The answer to how vitamin B12 and folate work together inside the body—and what actually constitutes “normal levels”—may explain why you’re experiencing symptoms like fatigue despite “normal” lab results. I personally learned this lesson the hard way after years of being told my exhaustion, brain fog, skin issues, and sleep issues were just my body reacting to stress, while no physician looked closely at my B12, folate, or iron status together

Later, when physicians did look, they continued to mark my levels as normal despite rapid declines compared to prior results, until my B12 and folate levels eventually became clinically abnormal. During this time, I experienced multiple cycles of B12 and folate depletion and repletion, and learned (both symptomatically and through research) what functional deficiency looks like for me, and how B12 and folate operate as a tightly linked metabolic system rather than isolated nutrients.

I ultimately turned to the research literature after a U.S. clinician dismissed my declining folate levels as irrelevant to my symptoms and attributed everything solely to “low-normal” B12. In contrast, a Colombian general physician I consulted was familiar with the body’s ability to recycle both folate and B12 and explained their interdependence—reflecting the stronger emphasis on nutrition and physiology in many non-U.S. medical training systems.

How Do B12 and Folate Work Together? More Than Just a Vitamin Duo

Together, B12 and folate drive one-carbon metabolism, a network of reactions essential for nucleotide synthesis, methionine regeneration, and regulation of methylation pathways.

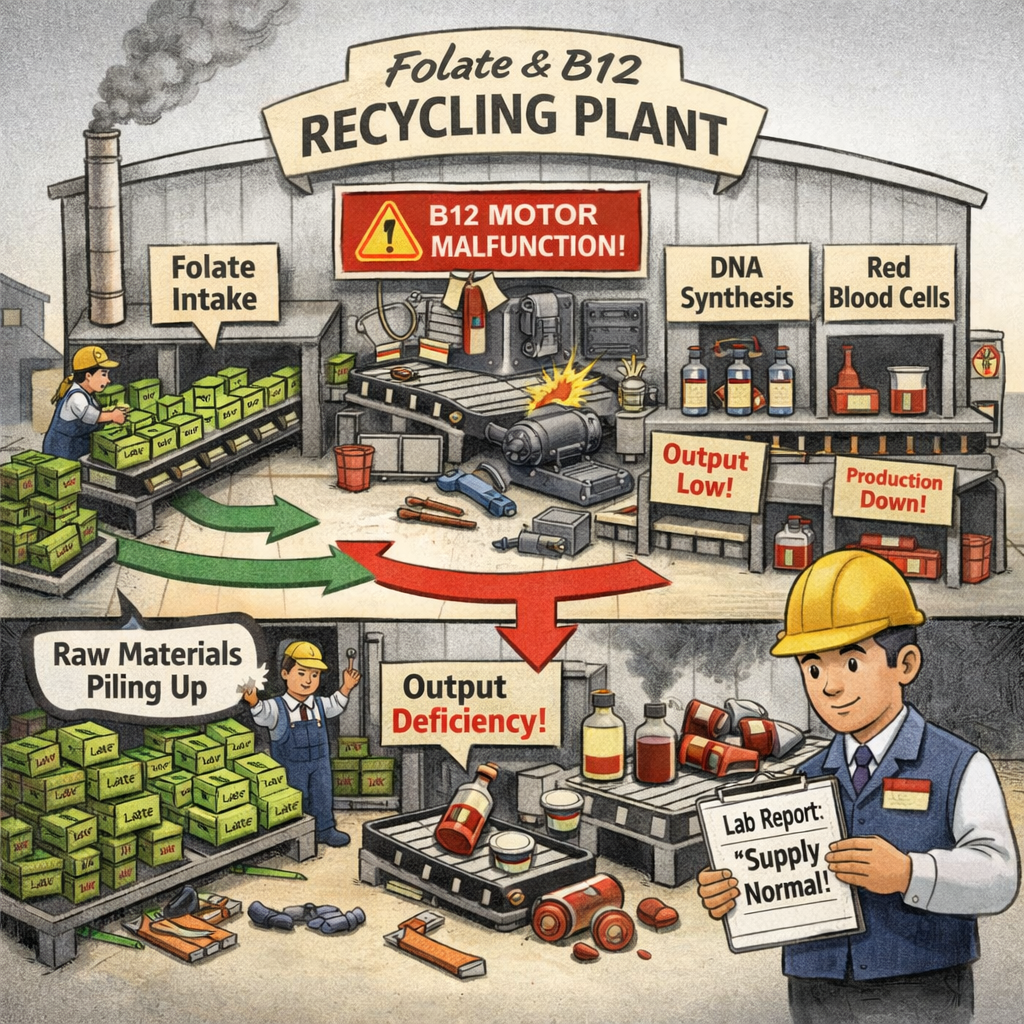

Think of B12 and folate as an inseparable biochemical pair. Folate (vitamin B9) provides carbon units needed for DNA synthesis and cell division, while vitamin B12 (cobalamin) enables folate recycling and supports red blood cell formation and neurologic function.

When this partnership functions well, people often feel mentally clear and physically energized. When this partnership is disrupted, symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive slowing, mood changes, and sleep disturbance can emerge, even when standard blood tests label levels as “normal.”

Why “Normal” Lab Ranges May Miss the Problem

The concept of “normal” is highly variable. Many U.S. laboratories report vitamin B12 reference ranges as broad as 160–950 pg/mL, even though values below about 200 pg/mL are widely recognized as deficient and 200–300 pg/mL are often considered borderline or insufficient, particularly when symptoms are present.

Some laboratories have begun adding interpretive comments noting that B12 levels between 200–300 pg/mL may be associated with deficiency symptoms and warrant further testing with methylmalonic acid (MMA).

Although some international clinicians and researchers use higher functional cutoffs (often about 500 pg/mL) in specific contexts, there is no single globally accepted “ideal” B12 threshold. What matters clinically is trajectory, symptoms, and functional markers rather than a static number.

In my case, my B12 dropped rapidly from about 750 pg/mL to about 450 pg/mL over several months after developing a spinal CSF leak. This decline was not flagged because the absolute value remained “normal,” yet I developed symptoms consistent with B12 insufficiency, such as perioral dermatitis, peripheral neuropathy, and cognitive changes, suggesting a functional deficiency relative to my prior baseline.

Folate Ranges, Sources, and Why High Levels Aren’t Always Pathologic

Serum folate reference ranges also vary by lab and by test type (serum vs. red blood cell folate). Many labs consider serum folate levels above 4 ng/mL (≈9 nmol/L) normal, while values above 20 ng/mL are often simply reported as “>20 ng/mL.”

Some literature suggests that elevated folate levels are most concerning when driven by a high intake of folic acid (the synthetic version of folate), which can circulate unmetabolized at high doses. However, other literature has stated that the data on the dangers of circulating excess folic acid from previous studies is inconclusive. Other causes for elevated folate levels can include genetic variants that impact efficiency in folate use. Some studies have specifically provided warnings on folic acid supplementation for pregnant mothers with genetic mutations, specifically those with the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T gene polymorphism.

In my case, my folate levels were high without folic acid supplementation, driven almost entirely by naturally occurring food folate from low-phytate sources such as avocados. Low-phytate foods improve mineral and folate bioavailability compared to high-phytate grains and legumes. Notably, I observed that folate intake from low-phytate foods produced larger increases in my blood serum folate than similar folate amounts from high-phytate grains, consistent with absorption research.

Why Folate Can Be High in People With MTHFR Variants—Even Without Folic Acid

High serum folate does not necessarily mean efficient folate utilization. The MTHFR enzyme converts 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate into 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF), the form used to remethylate homocysteine to methionine. Common variants such as C677T reduce enzyme activity, particularly under conditions of physiologic stress.

When MTHFR activity is reduced:

- Folate may accumulate in circulation

- Downstream methylation capacity may still be limited

- Homocysteine may rise despite “adequate” folate intake

This means that serum folate can appear high while intracellular folate flux is functionally insufficient, especially if B12 is also marginal. However, clinical research indicates that some individuals with MTHFR variants respond differently to folate forms, and that 5-MTHF may bypass a metabolic bottleneck in select cases.

What Is the Methyl Trap Hypothesis? What Is the High-Folate-Low-Vitamin-B12 Interaction?

The methyl trap hypothesis explains why B12 deficiency can produce functional folate deficiency even when folate intake is high. This hypothesis was primarily produced in a lab setting until a research study was able to demonstrate the presence of this hypothesized mechanism in a human patient.

Methionine synthase—an enzyme requiring B12—recycles 5-MTHF back into tetrahydrofolate forms used for DNA synthesis. When B12 is insufficient, folate becomes metabolically trapped as 5-MTHF, reducing availability for nucleotide synthesis.

This leads to:

- Elevated homocysteine

- Impaired DNA synthesis

- Altered methylation capacity

Interestingly, researchers have also explored a novel concept of the high-folate-low-vitamin B12 interaction. The methyl trap hypothesis and the high-folate-low-vitamin B12 interaction describe two related but different problems in how the body uses B12 and folate. In the methyl trap, B12 deficiency is the starting problem. When B12 is too low, an enzyme that needs B12 slows down, causing folate to get “stuck” in a form the body can’t fully use. Even if blood tests show normal or high folate, cells behave as if they are folate-deficient because folate can’t be recycled into the forms needed to make DNA. This explains why people with B12 deficiency can develop symptoms that look like folate deficiency, such as anemia, fatigue, and cognitive changes, even when they are getting enough folate.

More recent explorations on high-folate-low-B12 interaction describe something different. In this case, B12 is already low or borderline, and high folate intake (especially from folic acid) makes the B12 problem worse. Research shows that when folate is high and B12 is low, markers of B12 deficiency become more severe, meaning less active B12 is available to tissues like the brain and nerves.

In short, the methyl trap explains how low B12 disrupts folate use, while the high-folate-low-B12 interaction explains how high folate can worsen B12 deficiency once it already exists.

Functional Folate Deficiency: When Lab Results Mislead

This is where standard lab tests fail many patients. You can be in a state of functional folate deficiency while your folate levels are technically within the normal range because it's all trapped as unusable 5-MTHF.

I experienced it firsthand when my serum folate dropped from 18 to 8 ng/mL in just four weeks. That’s still within the “normal” range by most lab standards, yet I found myself battling symptoms like crushing fatigue, anxiety, and a terrifying disruption in my sleep-wake cycle where dreams bled into consciousness. It turns out that folate deficiency can alter melatonin secretion, which explains why the sleep aids I used only made things worse.

When I raised my concerns with a clinician, they fixated on my low B12 number and dismissed the folate drop. This is a common blind spot, as doctors trained in the US medical education system are trained to look for a single, glaring deficiency, which often leads to them missing the functional deficiencies caused by the imbalance.

Using Science to Combat Medical Gaslighting

Personally, I use a foundational knowledge of science gathered from the research to explore biochemical mechanisms to make greater sense of what I feel as far as symptoms.

My experiences with B12 and folate seem to not be rooted in a simple deficiency of one vitamin, but a shifting imbalance between vitamin B12 and folate that changes how I feel from day to day. When my B12 is already low or borderline, my body appears to slip into a functional folate deficiency, even when my blood folate has historically been high. This aligns with the methyl trap model described in the research, where limited B12 slows an enzyme needed to recycle folate into usable forms. In that situation, cells behave as if they are folate-deficient even though blood levels may still look acceptable. When clinicians focus only on whether a lab value falls within a reference range, this kind of functional deficiency can easily be missed.

I notice this most clearly when my folate drops quickly, such as falling from the high teens to single digits within a few weeks. When that happens, I don’t feel a slow, general tiredness like I do with low iron. Instead, I experience some days where I have intense, episodic crashes that come on suddenly around noon and can last for hours, with fatigue so strong it feels like my body might give out. Research helps explain why this feels different from iron deficiency for me. Folate is tightly involved in DNA synthesis, methylation, and nervous system signaling, so when usable folate becomes limited, the effects can be abrupt and destabilizing rather than gradual. Additionally, I often fast in the morning due to slow gut motility and waiting until I have a bowel movement to eat. The timing of this onset might be partially related to the length of the fasting period.

When I respond to those episodes by increasing natural folate intake, such as eating foods like avocados, my anxiety and energy often improve relatively quickly, sometimes within hours. That rapid response suggests I’m temporarily restoring folate availability to cells under strain. Because I do not take folic acid, my high folate levels would be coming from well-absorbed natural food folate rather than synthetic sources. However, once folate availability improves and perhaps I am overshooting highly bioavailable folate intake, another pattern becomes clear: the underlying B12 limitation and related symptoms becomes more noticeable. That is when I feel more classic B12-related issues, such as peripheral neuropathy. Research describes this kind of pattern as a situation where increasing folate in a B12-limited system raises metabolic demand and exposes or worsens B12 insufficiency rather than resolving it.

My Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) may add another layer that clinicians often overlook. While EDS is not a folate absorption disorder, connective tissue conditions are associated with higher metabolic stress and sometimes with genetic variation in pathways involved in methylation and one-carbon metabolism. A genetic variant would not necessarily mean that I cannot use folate, but it could make my system less tolerant of swings in folate and B12 balance and perhaps impact absorption and efficiency in use. That could explain why my folate has historically been very high, why sudden drops feel so severe, and why restoring folate calms my system quickly—yet also why B12 symptoms surface more clearly once folate pressure is relieved.

From this perspective, my symptoms are not contradictory or psychosomatic as clinicians have claimed. My situation instead reflects two well-described biological concepts interacting in a single body. The methyl trap helps explain why low or borderline B12 makes me feel folate-deficient when folate drops, even if labs still look “normal.” The high-folate-low-B12 interaction helps explain why raising folate unmasks or intensifies B12 symptoms when B12 is already compromised. When clinicians dismiss these symptoms because individual lab values fall within reference ranges, they may be missing a dynamic, functional imbalance that is very real at the cellular level.

Why a Holistic View Is Often Missing in Conventional Care

My experience highlights a frustrating trend in the U.S., where there’s a tendency to assess nutrients in isolation. Physicians often overfocus on Vitamin D, arguably due to influences from the billion-dollar vitamin D industry, while overlooking the larger picture of how vitamins and minerals work together and of looking at lab values over time.

Many women, myself included, report being gaslighted for years about symptoms like hormonal acne, irregular periods, and severe fatigue before anyone thinks to evaluate iron status and examine their B12 and folate levels as a pair.

In contrast to the U.S. approach, a Colombian physician I consulted with effortlessly described how the body recycles B12 and folate, and explained their interdependent roles. That foundational understanding of physiology is what’s needed to connect the dots between vague symptoms and treatable metabolic hiccups.

Navigating Your Own B12 and Folate Balance

So, what can you do if you suspect your B12 and folate levels are out of balance? It starts with self-advocating with your clinicians to get the right tests. You can discuss the following tests with your physician:

- Homocysteine (often elevated in B12/folate dysfunction)

- Methylmalonic acid (MMA) (a more specific marker for B12 deficiency)

- A full iron panel, including ferritin (stored iron), to rule out or rule in iron deficiency as a confounding factor

Next, address any deficiencies detected with your medical team. For example, boosting folate intake alone when you’re low in B12 can potentially worsen the methyl trap and strain your limited B12 reserves. I learned this when I noticed eating high-folate foods like avocados intensified my nerve pain while I was B12-deficient.

Additionally, B12 is not interdependent with iron as it is with folate, but I personally noted that a rapid increase in iron indicated by ferritin (stored iron) led to my body overzealously creating more platelets and pulling from my B12 reserves, creating a very quick platelet count jump from about 135,000 to 165,000 in two weeks but extreme peripheral nerve pain as my B12 was depleted. This is why it is important to make gradual changes that recognize how vitamins and minerals often work in tandem. At times, however, the body will do what it senses must happen for survival, and you may encounter hiccups as healing is rarely linear.

It is important to work with a knowledgeable clinician who understands how nutrients interact with each other to help address your deficiencies.

A More Holistic Approach to Addressing Nutrient Deficiencies

Are you tired of being told that your symptoms are "all in your head" when your body is clearly telling you that something is amiss? We're curating insights from international clinicians who specialize in an interconnected, physiological approach to healthcare.

Sign up for our newsletter for updates as we collaborate with more experts and share their insights with you.